Oonagh O'Hare is a Clinical Psychologist currently working in a Paediatric Psychology service in Leicestershire. Oonagh has previously worked as a trainee clinical psychologist within a Gastroenterology team where she became interested in IBD in young people and psychological well-being. This research study was completed as part of her doctoral training program in Sheffield. Anyone who was involved in the study originally and wanted to keep in touch with Oonagh, please contact us and we'll pass on your details.

You may have heard people say things like ‘it’s always darkest before the dawn’…and they may be on to something.

There have been many reports that after natural disasters, terrorist incidents, health crises and other difficult events, some adults feel changed for the better. Such reports fit with a concept called ‘Post Adversarial Growth’ (PAG). Other terms include post-traumatic growth, benefit finding or positive growth. PAG refers to a profound personal change in which individuals feel they have positively benefitted from adversity. It can mean different things for different people but can include a new outlook on life, a new found appreciation for certain things, new goals or paths in life or closer personal relationships. There have been suggestions that young people may not be able to experience such changes due to being younger and therefore having less deep-rooted ideas about the world. However my study suggests that young people with IBD can and do experience PAG.

Before going any further, it is important to note that what follows below is based on the stories of some young people with IBD but everyone will have a different story. If you haven't experienced PAG and can't relate to the concept, you aren’t doing anything wrong and it's not something you’re meant to experience – but it’s a possibility. By focusing on positive growth I was certainly not intending to trivialise the struggles that young people with IBD face. However, sometimes things can be both positive and negative simultaneously and this study shows that even after going through invasive surgeries, near-death experiences, harsh medications and painful and embarrassing symptoms, there could be positives related to some of these experiences. In fact, research suggests that in order to experience such a profound personal change, there must be some level of distress.

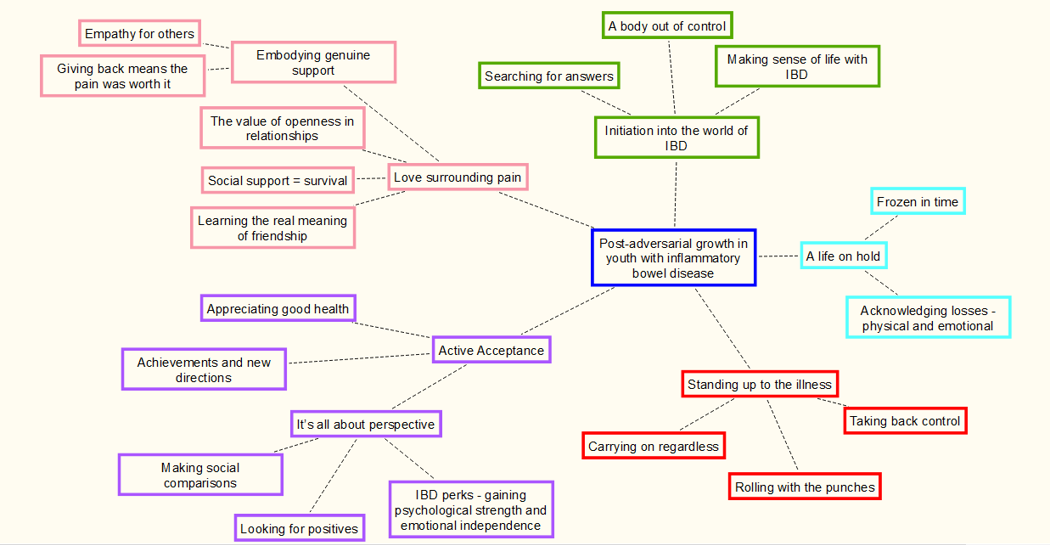

My study involved interviewing 14 young people around the ages of 16 to 25 who responded to an advert looking for people with IBD who felt their lives had benefitted in some way as a result of their condition. The interviews lasted around 45 minutes and were fairly un-structured, although all had the same basic questions encouraging them to share their story of having IBD. These stories were then typed up into scripts and the scripts were then read through many times and common themes were identified that could be used to understand the stories as a whole. This is a method of data analysis called Template Analysis. Below is a map of the themes and subthemes discovered and we will then look at the themes in turn.

The first part of everyone’s story was the ‘initiation to the world of IBD’. Across participants there was a shared sense that at the beginning of their lives with IBD, there was much to learn and adjust to:

- searching for answers: initially, participants searched to explain troubling symptoms, often struggling with symptoms being dismissed or misdiagnosed. Many participants had considerable periods of time left with this period of ambiguity.

my mum was researching online and she said ‘I really think my daughter’s got Crohn’s disease’, and my bloods were only showing slightly raised RP levels, but it wasn’t enough for them to consider it to be something major, it was ridiculous and it was 4 years of going back and forth, constant blood tests…

- a body out of control: around the time of diagnosis and beyond, participants reported ongoing symptoms or treatment side effects. Many participants reported significant challenges in learning to manage their condition such as being unable to tolerate food and the ongoing struggle with relapses and remissions.

So I realise I was a pretty nasty child to my parents anyway – then you realise you didn’t really have control over how you were acting, and it was the fact that I had no satiety when I was eating and I constantly craved these really high fat foods and I’d constantly – I’d be very demanding…

- making sense of life with IBD: most participants identified with not fully understanding what having IBD meant at first, sometimes only realising much later the impact it would have on their lives

I did a bit of research online. I think that I maybe felt a bit better after that because I was reading about all the treatments and things – at this point I still thought that they would put me on some tablets and I’d be normal again, I didn’t realise that there wasn’t ever going to be a normal, if that makes sense?

The second part of the stories seemed to fit with the idea that after being initiated into the world of IBD it felt like ‘a life on hold’. Participants described disruption to their lives whilst they adjusted to their condition, often feeling that they could not grow and develop as their peers could.

- frozen in time: participants described that following diagnosis they would often experience a period of stagnation; whether this was being housebound, not being able to carry on with work or education or losing independence.

I was saying to my mum, because sometimes we’d just be sitting in silence and she’d just say, ‘are you going to speak to me today’ and I’d just say ‘I’ve literally nothing new to update you on. Like you know everything that’s going on, nothing new has happened, I’ve got nothing, literally nothing in my head to say’.

- acknowledging losses – physical and emotional: participants were aware of the losses they had experienced because of IBD. Many gave up hobbies, career plans or educational goals. For others, the losses were more emotional such as feeling left behind.

It was quite crushing to be told I couldn’t pursue a career in what I wanted to do…when I kind of had my dreams set on that, because I was a gymnast and I could have joined the navy, etc. But I wasn’t allowed. Um, so yeah, quite a big impact, but I tried to stay positive, but I got on the course I wanted to do.

The third part of the participants’ stories was ‘standing up to the illness’. Participants’ early experiences with IBD seemed to foster defiance towards the condition and what it had done to their lives.

- carrying on regardless: there was a strong sense that participants became determined to carry on with life despite having IBD whether this was due to being unaware of the severity of their illness or due to a determination to live as normally as possible;

for myself it was difficult to sort of appreciate how ill I actually was, because I was always a really outgoing, a really kind of active person, so I just kind of got on with it.

- taking back control: participants regained control where they could. Learning to live with IBD meant that participants knew themselves, their bodies, what they could withstand and what treatments would work best for them.

...and also kind of taking responsibility for your own health because I think a lot of people ‘oh well I’ve got Crohn’s I’m poorly and that’s it’ whereas I thought, no, I’m going to exercise and sleep a lot, I’m going to go vegan, I’m going to change my lifestyle...

- rolling with the punches: although participants expressed the desire to carry on despite the barriers IBD placed in their way, there was the need to adapt and modify things somewhat in order to work around the condition.

I always wanted to do the usual thing; finish uni, do a gap year, obviously that didn’t happen…-and that was it, so I left, no gap year and that’s how it is, just deal with it, to a point where now, work notwithstanding, I will be taking extended holidays up to fairly faraway places, just – I’ll just know how I need to manage it more, I’ll just take more precautions. Fine, it may not be as long as I want to be, but do you know what, I’ll still get to the vast majority of the places I want to get to, just in more trips.

The fourth part of the stories was around ‘love surrounding pain’. This was a strong theme; that social support was vital to being able to live a fulfilled life with IBD.

- learning the real meaning of friendship: many participants found their relationships with friends or partners strained following their diagnosis. Some felt they could no longer maintain these relationships due to a realisation that they had less in common than previously. However, many reported finding new friends where there was a deeper connection;

when you’re in such a state, like I had been, you see the beauty in the world, you see the beauty in people and the beauty in people’s ways of how they can help you just to feel strong. Like last year, my friends would come in (to hospital) every week, and we’re all music students, so they’d all sing with me and just keep me going and that’s a beautiful thing that you have to take.

- social support = survival: support from others, particularly family members, was essential, whether this was to provide emotional support, financial support or to provide the right environment under which they could get their condition under better control. Many felt that this, along with positivity and encouragement, was a crucial facilitator of experiencing PAG.

They’re just great, I don’t know how to describe it. They come to appointments with me, ask all the questions I’d probably forget to ask, make sure that I’m taking my medication, remind me about it 50 times a day because I’m forgetful.

- the value of openness in relationships: IBD is largely an invisible illness. It also causes many embarrassing symptoms. For this reason, some chose initially to keep their condition private from the outside world. However, it seems that participants found it beneficial to have some people with whom they could be open about their condition. This led to valuing honesty and openness.

I would say it has definitely strengthened my relationships as well. I think maybe at first I was kind of embarrassed about it, but then my friends were very supportive and a couple of them studied medicine-type things and then they were really interested about the disease and stuff, so it helped make it more of an open conversation; you didn’t have to be awkward about your symptoms and what was going on.

- embodying genuine support: one of the ways in which many participants felt they had grown was in offering support to others. This seemed to be in two ways:

- empathy for others and recognition of the invisible: participants understood that their health, whilst largely invisible to others, impacted greatly on their mood and behaviour and that this could be the case for others.

I think I’m a lot more – this is what my mum calls it – emotionally intelligent, so I’m very aware of other people’s emotions and how they react to stuff. I’m always the kind of person that says even if someone’s really angry or doing something negative, there might be something going on behind the scenes that you don’t know about, because having this condition makes you so aware that there are people with invisible illnesses and you don’t know what people are struggling with, so don’t judge them straight away.

- giving back means the pain was worth it: many participants derived a sense of purpose and meaning from being able to share their experiences with others who were diagnosed with IBD and to be able to show them a positive outcome.

I think because my story has been so big, I’ve been able to reach it out to everybody else. I’ve been able to speak about it to a lot of different people which has brought other people positive growth as well

The final part of the stories was active acceptance. Although participants first experienced the difficulties of IBD, all participants came to view their condition positively and actively embraced life with IBD.

- achievements and new directions: despite the barriers, participants worked hard for academic achievements, to reach goals, try new hobbies and find new careers. For some, it was the barriers that increased the value of the things they had achieved.

…for a little while I wasn’t sure that I was going to get through it, just because I was quite stressed about it, how to manage the workload as well as the illness. I think going from there and then kind of calming down a little bit and just focusing on the work and then I managed to still do quite well, even though I had to have an extension and things like that, so that kind of made me more proud of it in a way, or it made it seem more worth it.

- appreciating good health: participants all felt appreciative and made the most of their health, particularly when they felt their condition was well managed or in remission.

I really appreciate my food, I really like – even if it’s just a bowl of soup, it’s amazing that I can eat it because I’ve been, I’ve had so many times where I’m starving to death

- it’s all about perspective: there was a strong theme that a positive outlook had helped participants to manage their condition and any stumbling blocks as well as being important for helping them feel that they had benefitted from their condition. Perspective was gained in a number of ways:

- making social comparisons: a common way that participants achieved this was to compare themselves to the challenges of others or even themselves earlier in their journey with IBD.

I try and look on the positive side of things. There are people who are in a lot worse condition than I am, with my condition. There are people who are in hospital every week and I’m lucky to not be in that.

- looking for the positives: participants also generally looked for positives in their situation, which brought them comfort and strength.

It’s not always about how damaged you are…but if two people have the same illness and one was positive about it and would do everything they could to almost fight it and the other just gave up, it just changes so much

- IBD perks – gaining psychological strength and emotional independence: the difficulties of IBD helped participants develop resilience and feel that they could take on future challenges more successfully.

I think it makes you maybe more resilient if you face other set-backs, even in work or academic life that you know that you do have the strength to get through it, even though it seems really daunting at first.

In summary, despite describing many ways in which IBD was a difficult experience in their lives; disrupting life even before they received their diagnoses, participants described being able to move forward and gain positives from their experiences. What seemed to help participants to achieve PAG was successfully navigating and adapting to life with IBD with help from friends and family. Participants came to view IBD as a positive influence in their lives; reporting closer and more meaningful relationships, appreciating good health, being able to receive help and offer support to others as well as gaining psychological strengths.

As I mentioned above, this might not happen for everyone. The group of people who I spoke to might represent an exceptionally positive group. Further, one thing that is less clear from the study is how long it took the group to find benefit from their experiences – their stories all suggest that it had taken some time from first being diagnosed to being able to acknowledge benefits and growth but some might have got to that point quicker than others. It could be that there were certain milestones in their journey that were key turning points. Exploring this might have led to a better understanding of the process of PAG. If this study were to be repeated, this would be something to look into.

As a researcher looking into life with this condition, I was incredibly grateful to the participants for sharing their stories with me. It was a true privilege and hearing about their journeys with IBD made me feel stronger – so I hope that by reading this you are able to take some of that strength too.