by Dr Protima Amon, Consultant Paediatric Gastroenterologist, Barts and the Royal London and CICRA Fellow at the Blizard Institute

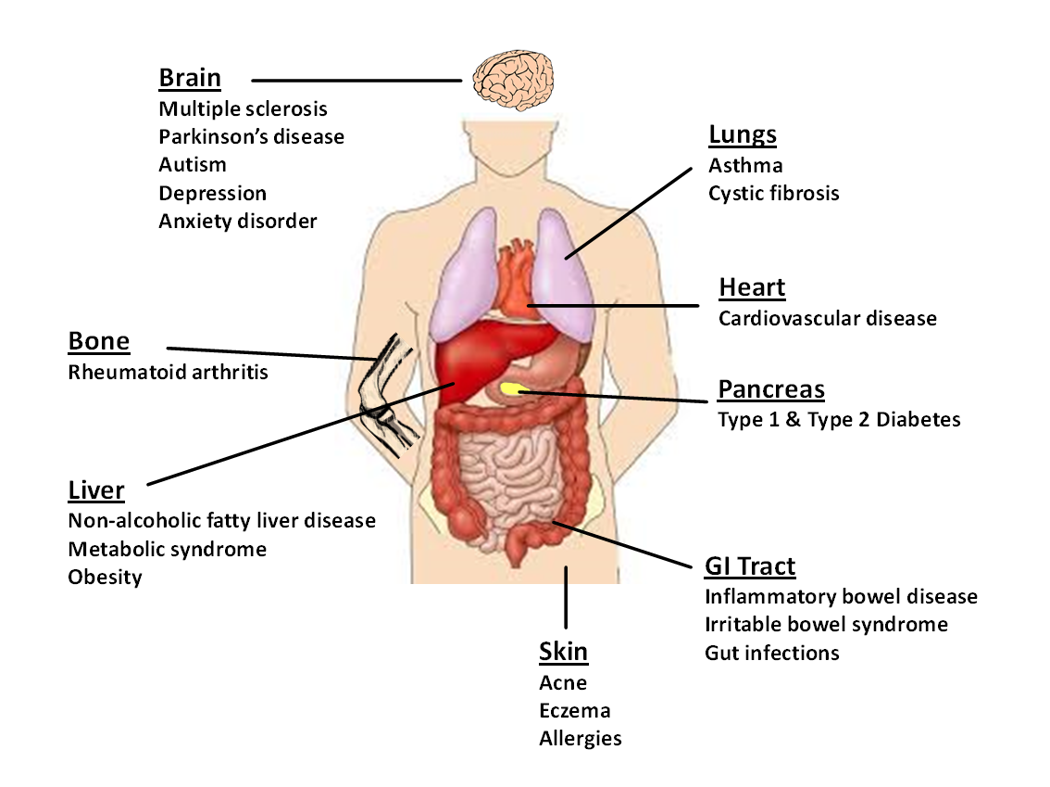

As a gut doctor, my main interest is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). I have spent a lot of my working life pondering this condition and inquiring about causes, treatments and possible cures. As I approached the end of my training in 2014, a particular hot topic that was emerging was the role of gut bugs, termed microbiota in health and disease. I recall feeling very gripped by the research articles I read at the time. There was growing scientific evidence suggesting that changes in the microbiota were implicated in diseases such as diabetes, asthma, heart disease as well as IBD [Fig 1].

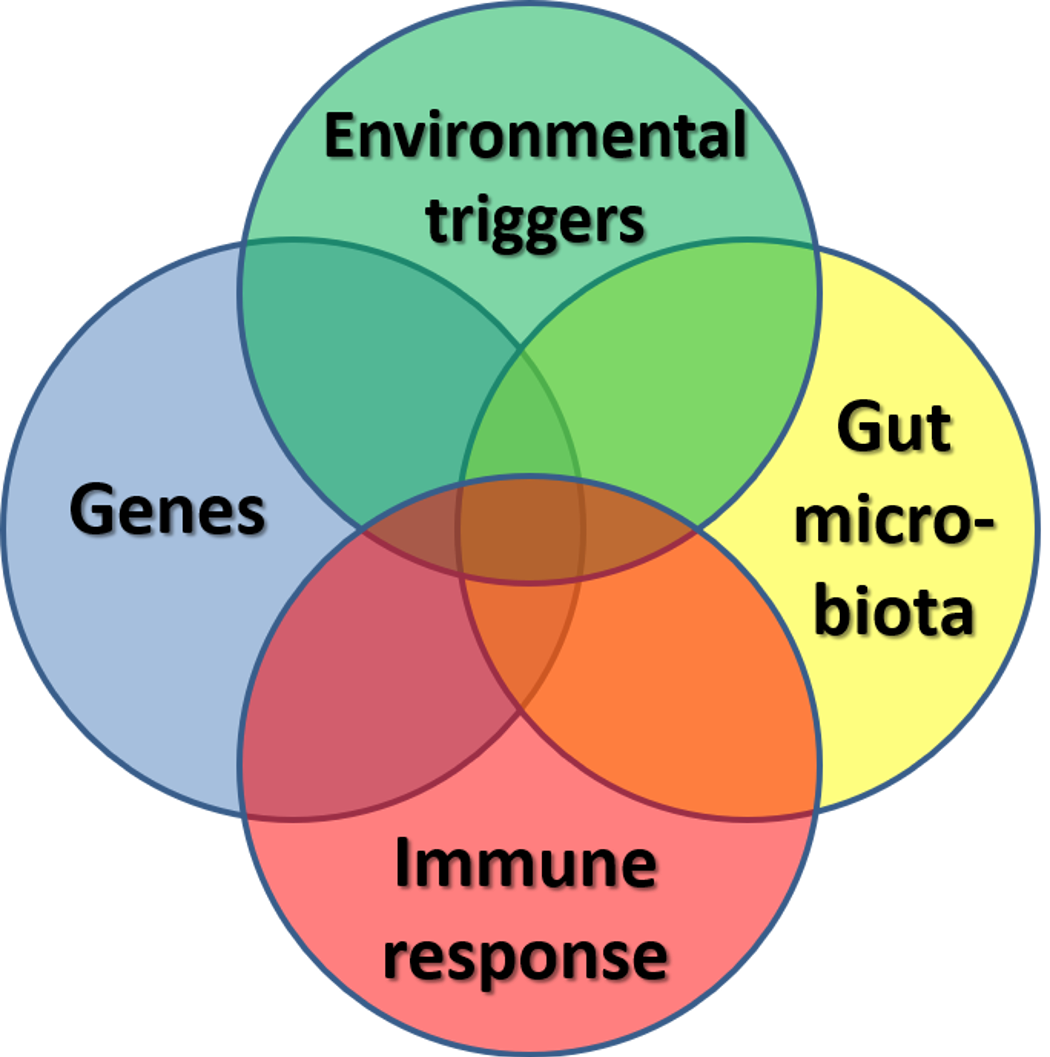

IBD remains one of the most extensively studied human conditions associated with the gut microbiota. It was around this time when I made one of the most life changing and rewarding decisions in my career to date. I became so interested in exploring the role of gut bacteria in childhood Crohn’s disease that I decided to step into a scientific laboratory. I am grateful to CICRA for funding my research project and for giving me this opportunity to write about the research I do. Although the cause of Crohn’s disease remains elusive, the generally accepted hypothesis is that multiple factors are involved. Crohn’s disease is thought to be the result of interaction of genetic, immunological and environmental factors, notably the gut microbiota [Fig.2].

With the recent advancement in next generation sequencing technologies, scientists including myself are now able to investigate the composition and dynamics of the microbial communities which mainly reside in the gut. Studies of their intestinal gut microbiota in Crohn’s disease patients imply that an unbalanced microbial community composition is associated with a disturbed immune response.

The results from my study are in keeping with published research, which identifies a reduced bacterial diversity in people with Crohn’s disease. This reinforces the notion that gut microbiota is implicated in the cause of Crohn’s disease. However, the relationship between changes in microbiota composition and disease causation remains uncertain. The challenge is to identify whether microbial imbalance is related to disease, sometimes termed “dysbiosis”, and to be able to distinguish between cause and effect.

Over the course of my study, I understood this area of research is complex not just in terms of methodology but also when reporting correlation versus causation and describing diversity.

In a healthy state, it is reported that humans have a very rich diversity of organisms. However, each person will have a different microbiota profile, which suggests there is no single ‘healthy’ microbiota composition and each person will have an individual relationship with their own microbiota. It is also known that differences between microbiota compositions exist depending on age, cultural background and geography. So far, the patterns of gut microbiota dysbiosis in Crohn’s disease are inconsistent in published studies and there remains much that is not understood. So although this field is exciting and rapidly moving forward, there are plenty of challenges we face when trying to solve the enigma that is Crohn’s disease.

Moreover, we do not yet have a cure for Crohn’s disease and the treatment options are limited, particularly in children. Most children require treatment over the long term and the current medical therapies that include corticosteroids, 5-aminosalicylates, antibiotics and potent immunosuppressive drugs have significant side effects. Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) is recommended as induction therapy for active paediatric Crohn’s disease in UK and across Europe. Enteral nutrition involves the administration of a liquid diet formulation, which is either elemental or polymeric formula. Enteral diet has strong anti-inflammatory effects when given exclusively for 6-8 weeks, without any additional foods. This treatment is our most effective therapy, in terms of safety and efficacy, but we still do not completely understand how enteral nutrition works and what impact it has on the gut microbiota. This is a particular focus in my current research project.

I am testing the hypothesis that EEN effects are primary on microbiota and not secondary to inflammation. There have been some research studies which suggest changes in the microbiota as a possible mechanism of action of EEN. In the work I am doing, I propose that EEN is efficacious by altering microbial diversity and community membership in Crohn’s disease patients. I feel very privileged to have the opportunity to combine my clinical interest with a scientific career. The work balance is constantly evolving and can be tough at times. However, I am excited and hopeful that my study will lead to important results which are novel (e.g., changes in microbiota are a result of EEN and not an effect of inflammation).

In addition, the description of specific changes in certain microbial species at disease onset and following EEN may offer clues to disease causation and have potential therapeutic implications in the future.

If changes in the microbiota are associated with remission, future studies will try to maintain that microbiota with the possibility of achieving long-term remission in children with Crohn’s disease.

Great news for young IBD patients - Dr Protima Amon, now finishing her 3 year CICRA funded fellowship, will continue her fascinating work uninterrupted as a consultant, awarded whilst she was a CICRA Fellow.